Decomposition and Changes in the Dead Body: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction

The death of living beings is followed by series of interesting physical and chemical changes in the dead body. While unpleasant, studying these post-mortem changes helps us understand the mysterious process of decomposition and various associated phenomena. In this guide, we delve deep into various stages of decomposition and analyze physical transformations afflicting a cadaver over time.

Rigor mortis and Muscle Stiffening

Shortly after death, muscles in the lifeless body lose their tone and stiffness. However, within few hours, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion in muscle cells triggers their contraction and stiffening - a phenomenon known as rigor mortis. It starts from smaller muscles of face, neck and extremities and slowly envelops larger muscles. Rigor mortis peaks around 12-36 hours post mortem and gradually dissipates over next 3-5 days as cells lose ability to maintain contraction.

Production of Gases and Bloating

With cessation of critical bodily functions like respiration and circulation, tissues are deprived of oxygen rapidly. However, anaerobic bacteria indigenous to digestive and respiratory tracts remain viable and breakdown tissues liberating noxious gases like hydrogen sulphide, carbon dioxide and methane as byproducts. Accumulation of these internally causes bloating and swelling of the abdomen hours after death. On sufficient build up of internal pressure, gases escape via natural orifices with noises.

Changes in Skin and Soft Tissues

As tissues break down, skin begins to pale taking on a waxy, marbleized appearance due to settling of blood in dependent portions known as livor mortis or lividity. Skin becomes vulnerable to slippage and detachment aided by cutaneous microorganisms and insect larvae. Concurrently, body cools at around 1°C per hour until matching ambient temperature.

Putrefaction and Further Decomposition

Putrefaction ensues with proliferation of anaerobic bacteria in tissues causing them to liquefy and exude putrid fluids, aggravating fouls smells. Fluids released can form decomposition fluid islands around the body known as “Black Putrid Blood”. Over weeks, soft tissues rot away leaving only bones. Concurrently, various scavengers and carrion-eating insects invade accelerating rate of disintegration.

Stages of Decomposition

Decomposition progresses through predictable stages influenced by numerous environmental factors. Let’s explore these stages in detail:

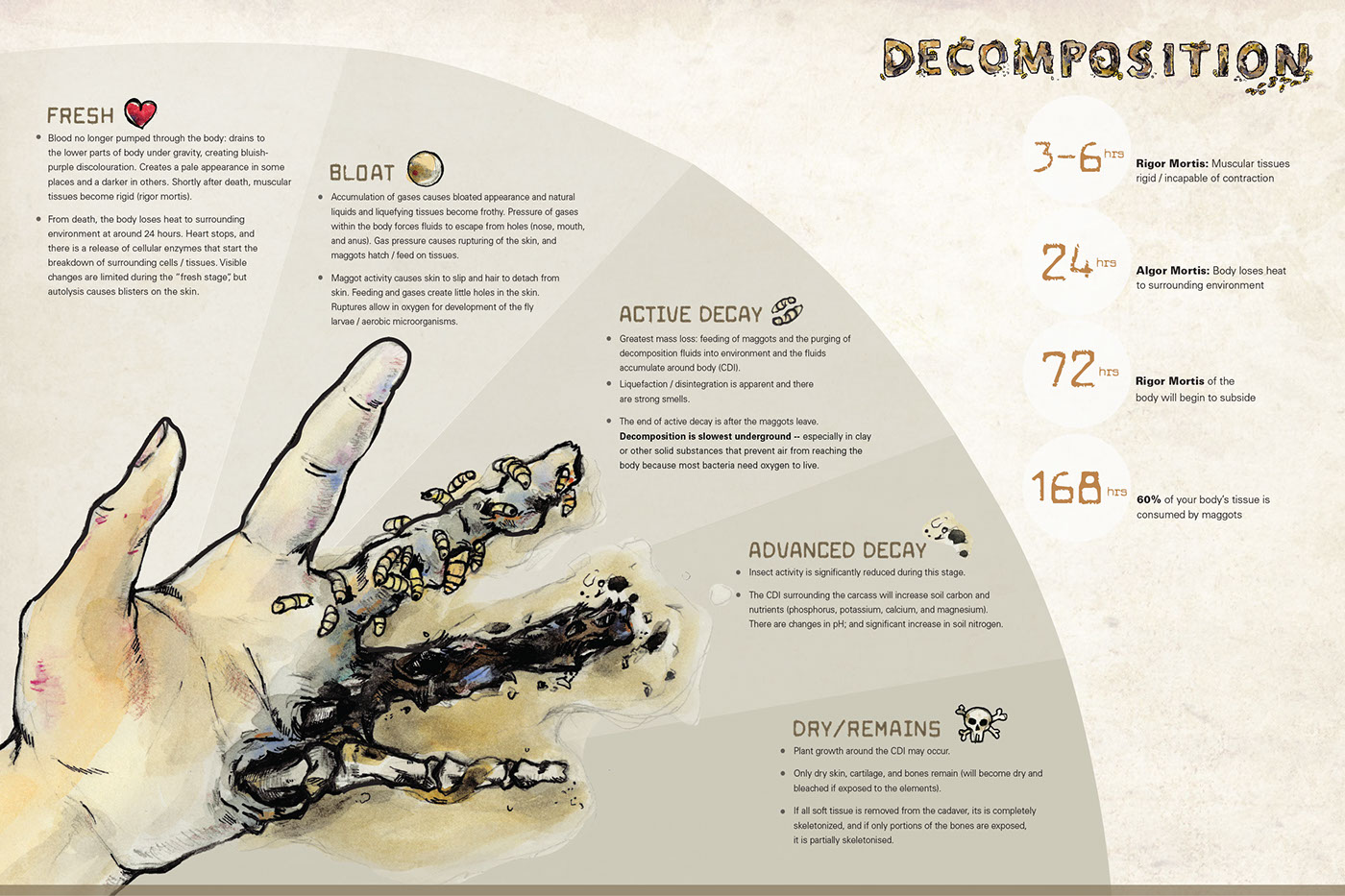

Fresh Stage

Hours post mortem, the freshly dead body enters a stage called fresh or early decomposition. Distinguishable changes are largely biochemical mediated by autolytic enzymes. Muscles stiffen as rigor mortis sets in. Skin lacks pallor mortis taking on natural color.

Bloat Stage

Within 2-4 days, anaerobic respiration of intestinal microflora build up noxious internal gases causing body to bloat and purge fluids from natural orifices. External sniffing blows flies and other carrion insects are usually the first to arrive.

Active Decay Stage

Over next 1-2 weeks, putrefaction peaks as aerobic bacteria break down tissues at high rates assisted by maggot activity. Body mass reduces rapidly with release of foul-smelling fluids. Skin slips and tears expose deeper tissues.

Advanced Decay Stage

As readily degradable tissues are consumed, decomposition slows entering advanced decay lasting 2-4 weeks. Remaining are remnants of dry skin, cartilage and bones. Ecosystem disturbances from initial decomposition subside.

Dry/Remains Stage

Over months, remaining tissues are lost to environmental factors leaving behind dry, bleached bones fully skeletonized. Nutrient levels in surrounding soil normalize as ecosystem recovers completing the decomposition cycle.

Factors Influencing Decomposition

Several external parameters alter decomposition pace like temperature, moisture, insects/scavenger access, depth of burial, trauma etc. Let’s explore some key factors:

Temperature

Warmth exponentially boosts microbial and insect activity hence decomposition rate. Frozen tissues on thawing resume putrefaction more vigorously than naturally.

Moisture

Putrefaction demands aqueous fluids but excessive wetness induces anaerobic conditions slowing process. Optimal is damp environment ensuring aerobic bacterial proliferation.

Insect Activity

Carrion insects like blowflies and flesh flies are among first to colonize feeding and ovipositing on tissues. Maggots excrete digestive juices and hormonally induced weight loss accelerating decay.

Burial Depth

Shallow burial permits insect/scavenger access maintaining warmth and moisture hastening decay. Deep entombment impedes access preserving tissues for years by limiting factors.

Trauma

Ante- or post-mortem injuries compromising tissue/skin integrity facilitate microbial ingress shortening time to skeletonization. Conversely, integument preservation delays access.

Environmental Preservation

Some settings arrest decomposition like cold arctic/alpine regions, arid deserts and waterlogged anaerobic soils yielding natural mummies over centuries. Factors vary preservation potential.

Conclusion

Death unleashes complex biochemical and microbial transformations in the human body gradually reducing it to basic elements. Understanding decomposition stages and factors is vital in forensic and medical analysis. While macabre, appreciating our mortality fuels scientific inquiry and closes life’s cycle.